By the measure of whether companies “beat” estimates, the most recent U.S. reporting season was outstanding. At our last count, 79 per cent of S&P500 companies had exceeded consensus estimates.

With the S&P500 at record highs, easy monetary conditions, another fiscal stimulus package and reopening ahead, perhaps that’s all equity investors need to know.

But, as we look more closely at earnings trends in the U.S. market, what becomes clear is that companies are increasingly making adjustments that boost official earnings numbers – and at times, mask the underlying business reality. So, exactly what earnings are beating estimates?

In this article, we will look at how some companies are using adjustments to inflate earnings, the escalating use of adjustments, and lay out why all this matters for investors.

A brief historical context

In short, adjusted earnings are financial metrics that don’t meet the relevant U.S. accounting standards for inclusion in financial statements. For those that don’t spend their time digging through listed company financials, adjusted earnings are often provided in company’s earnings press releases, and in investor presentations and calls, which are less heavily regulated than the standardised, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (or GAAP) earnings found in financial statements (1). We will refer to adjusted (or non-GAAP) earnings and GAAP earnings throughout this article.

Adjusted earnings should help improve the visibility of the core business’ performance and sustainability. A one-off event involving a large legal settlement may blur the picture of a company’s underlying health. For example, when rating agencies Moody’s Corporation and S&P Global added back settlements following the Financial Crisis and subsequent industry reform, it provided a clearer view of core businesses that remained incredibly profitable.

However, adjustments are nuanced and may be misleading. Unsurprisingly, some management teams have, at times, gamed the system, making questionable adjustments to earnings to give the appearance of higher profitability. A former Chief Accountant at the Securities and Exchange Commission, Lynn Turner, succinctly described non-GAAP earnings as reporting “everything but the bad stuff”.

One of our favourite examples in recent years was the adjusted earnings manufactured by WeWork, the provider of shared office space. The company’s 2018 offering document caught our attention with the very creatively titled “Community adjusted EBITDA”. This inflated earnings by adding back almost every imaginable expense including stock compensation, rent adjustments, sales and marketing costs, growth and new market development expenses, as well as general and administrative expenses, magically transforming 2017’s EBITDA loss of $769 million into a profit of $233 million.

In the long run, of course, trouble awaits managements that paper over operating problems with accounting manoeuvres. Eventually, managements of this kind achieve the same result as the seriously-ill patient who tells his doctor: "I can't afford the operation, but would you accept a small payment to touch up the x-rays?"

Berkshire Hathaway 1991 shareholder letter

WeWork’s 2018 disclosure was a harbinger of a failed 2019 IPO. The valuation halved, before the IPO was pulled, and subsequently WeWork was acquired by its largest investor, Softbank, to help the company avert bankruptcy. As The Guardian noted in December 2019 this was “facilitated by the public exposure of long known information: WeWork was losing a ton of money …” (2).

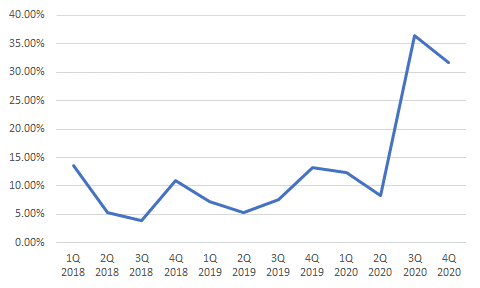

Recent data on adjusted earnings confirmed our suspicions about the increasing frequency and magnitude of adjustments. The data also lends support to the claims that overall, adjustments rarely reduce reported earnings. It seems once on the adjusted earnings treadmill, getting off can be difficult.

Median adjusted EPS boost (to GAAP EPS) for the Dow Jones Industrial Average

Source: FactSet and Claremont Global

While COVID-19 may have resulted in genuine one-offs, the trend for greater use of adjusted earnings is clear. Management adjustments are becoming more prolific. In 1996, 59 per cent of S&P 500 companies used non-GAAP metrics by 2016 that had increased to 96 per cent (3).

Recent advances in augmented reality

Two categories of adjustments that we monitor closely are restructuring and stock compensation add-backs.

Restructuring charges are a common adjustment. From time to time we see justifiable earnings adjustments by the management of our portfolio companies as they navigate one-off events. Conversely, repeated restructuring charges are a red flag; flattering adjusted earnings and potentially masking significant and very real, day-to-day expenses.

Stock compensation add-backs are another frequent adjustment, particularly in the tech sector. Ironically, while the early 2000’s accounting requirement that companies expense stock options has been complied with to the letter in financial statements, many management teams now add back all stock compensation to adjusted earnings.

In our view, this provides a misleading view of profitability. Take for example SNAP Inc (SNAP), the social media company. We have no gripe with SNAP, the company has excellent traction with products, users and increasingly advertisers, however, their large equity compensation plan does highlight an existential expense question.

In 2020, SNAP’s stock-based compensation was $770 million, or 30 per cent of revenue. In comparison, adjusted EBITDA was only $45 million, and that was after adding back over three-quarters of a billion dollars in stock expense. One single adjustment shifted a lot of red into the black (at least on an EBITDA basis).

Does adding back recurring stock compensation really provide a better indication of SNAP’s true underlying performance? Stock awards are key to attracting and retaining SNAP’s talent. As at the end of 2020, SNAP had almost 4,000 full time employees, with over half in engineering roles. Good luck competing against Facebook (4) after cutting $770 million from your yearly compensation bill, in the intensely competitive, Silicon Valley labour market. In fact, in SNAP’s 10K disclosure the risk factors indicate that even a share price decline poses a risk to both staff motivation and retention. Fortunately for SNAP, most analysts covering it focus on revenue multiples!

While various adjustments from Uber, Tesla and Alibaba have at times caught our attention, it would be a mistake to tar all tech companies with the same brush. Alphabet and Microsoft are two companies within our portfolio that heavily utilise stock compensation, yet always account for this as an expense. Neither of these companies embellish GAAP earnings with adjustments, they’re already highly profitable businesses.

Perverse incentives and outcomes

So, does it really matter that some companies are including more aggressive earnings adjustments and subtly shifting attention to non-GAAP earnings? We think it does.

Firstly, earnings measures preferred by management may obscure key business trends and comparability across periods (when adjustments are conveniently applied inconsistently) and across companies. Diligent investors and analysts may be expected to see through such dubious adjustments. However, it’s a fast-paced, headline-driven, and currently credulous market, where momentum and all-time highs cover a multitude of sins. Details just get in the way of making money in the short-term.

Perhaps more concerningly, many senior management teams are highly incentivised to touch up their own x-rays, through performance-based compensation linked to adjusted earnings metrics (and comparison to other companies who also utilise adjusted earnings). Management compensation plans, disclosed in U.S. proxy statements, highlight the breadth of companies paying CEO’s based on one form or another of adjusted earnings (5). This risk was highlighted by a 2018 study that found “CEO pay is excessive for the S&P 500 firms that report non-GAAP earnings that are much higher than their GAAP earnings”(6).

The long game

As the frequency and magnitude of earnings adjustments continue to grow, so does the risk of tipping points for companies whose adjusted earnings no longer even vaguely approximate the financial reality. This may happen either through tougher regulation or perhaps more likely, through a dawning realisation in a less buoyant market, with a subsequent loss of investor confidence and capital.

One day the market woke up and said, yeah but these numbers don’t make any sense.

Andy Fastow Former CEO of Enron

It is exceptionally difficult to precisely time dramatic shifts in market perception. So, dancing until the music stops is a waltz we’ll leave to others (7).

But there is an upside. Questionable adjustments may signal underlying business operations that are struggling to meet expectations and a management culture that encourages half-truths or denial, that we’re happy to avoid. All of which is invaluable information to fundamental investors with a long-term horizon.

At Claremont Global, we construct our portfolio on four key pillars: business quality; management quality; robust balance sheets; and a keen focus on valuation. Earnings quality, backed by strong cash flow, is key to our investment process, as it affects each of these four pillars. We will continue to pore over adjustments (as well as less obvious accounting manipulation) as we evaluate businesses, valuations and management teams.

Unlike some boards, we don’t rate management highly for consistently achieving targets through fanciful financial adjustments. Rather, we expect management teams at our portfolio companies to be focused on taking steps today (and tomorrow, and the next day…) to improve the core business and compound returns over the long-term. In a concentrated portfolio of 12 to 15 securities, no company is there to make up the numbers.