With a mandate of owning 10-15 stocks, I am often asked: “How do I sleep at night given the concentration risk?” This has been a familiar refrain for most of the 25 years I have been managing client capital and where I have always run concentrated portfolios with 10-25 stocks. The thinking suggests that with a concentrated portfolio, you are running excess risk and one would be better served having a more “diversified” portfolio.

My answer is always the same – it all depends on how you define risk.

If you define risk as the chance of underperforming an index or benchmark in the short term – then I would agree this is “risky”. This is the classic fund manager’s “career risk” – the chance of underperforming a benchmark and putting your job on the line or losing client FUM. In the words of John Maynard Keynes:

It is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.

But to earn returns that are better than the market, it is really quite simple - you have to own portfolios that are different from the market.

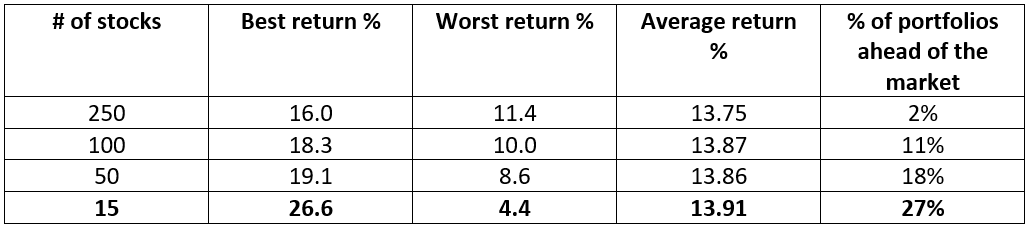

Robert Hagstrom in his excellent book The Essential Buffett – timeless principles for the New Economy ran a 10-year study from 1987-96 where he had a computer randomly assemble 3,000 portfolios from 1,200 companies and broke the results down as follows:

It is interesting to note the 15-stock portfolio achieved an average return not much different to the 250-stock portfolio but with a much wider range of outcomes (i.e. much higher career risk!). However, the chances of beating the market were also more than 13 times higher. In addition, Lorie & Fisher showed in their 49-year study of NYSE-traded stocks between 1926-65 that 90 per cent of stock risk can be diversified with a 16-stock portfolio.

But we define risk as the possibility of permanently impairing client capital or not achieving a satisfactory return for the risk taken. And we target a long-term return of eight to twelve per cent per annum over a five to seven-year period.

We believe a permanent impairment to capital is most likely to arise in the following ways:

Buying heavily leveraged businesses

Many management teams are very happy to layer on debt in the good times by “returning capital” to shareholders and achieving artificial EPS growth to satisfy short-term and poorly defined incentive targets. There is no better example of this than the actions of American Airlines in the five years to 2019. The company “returned” $13bn in buybacks - this was despite the fact there was no capital to return, as free cash flow over the period was a NEGATIVE $3.2bn! The ratio of debt to earnings before income, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) was 4.2-times in 2019 at the peak of the cycle.

In our opinion this is highly irresponsible, given the industry already has a high degree of operational gearing, has a large amount of off-balance sheet debt in the form of leases and is vulnerable to rising oil prices. And then when tough times hit, these companies go cap-in-hand to the government and/or shareholders to repair balance sheets at very depressed equity prices, resulting in severe value destruction.

By contrast, our portfolio has a weighted net debt/EBITDA of 0.7x. Excess leverage is just not a risk we are willing to run. Balance sheet strength is a given in our portfolio. We know that the future is always uncertain and rather than trying to forecast when the good times will end (folly in our opinion), we assume that recessions are a natural part of economic life and we prepare accordingly.

The added benefit of this is that when recessions occur, our companies can play offence – buying quality assets or their own shares at favorable prices and maintaining or even increasing the dividend. We have companies in our portfolio that have consistently paid rising dividends for over 40 years.

Buying businesses that rely on an accurate forecast of some hard-to-predict variable

These variables can be interest rates, moves by the Federal Reserve, commodity prices, regulation, innovation and election results, amongst many others in a complex world. In 2016 I didn’t know many people who predicted Trump would be elected ― and for those who did, how many predicted that markets would rally? Or in March of this year, who would have thought the market would be at an all-time high in December, when the global economic contraction has been the largest since the Great Depression?

Another favourite of mine in recent years has been buying banks on the “yield steepening trade”, only to then see rates collapse. Or the oil majors in 2014, who spent billions on exploration with a forecast of oil being above $100 a barrel, only to see oil collapse with the advent of shale oil.

We deliberately avoid businesses that rely on us correctly forecasting commodity prices, interest rates, elections, drug discoveries, economic growth or political outcomes. Experience has taught us that very few people are able to do this on a consistent basis.

Yogi Berra put it well:

Forecasts are hard, especially about the future.

Buying inferior businesses with no competitive advantage

Over time, competition does a pretty good job of taking away excess returns for most businesses. And over time, it is very hard for an investor to earn a return much different than the underlying economics of the business one owns. If an investor wants to earn an excess return, logic suggests that the best place to start is with owning businesses that themselves earn excess returns on shareholder capital. Superior returns on capital normally arise from some form of competitive advantage – be it a brand, network effect, scale, reputation, data, client relationships, IP or technology. But the allure of buying “cheap” businesses is often too much for some. Even Warren Buffett himself made this mistake when buying textile company Berkshire Hathaway at a steep discount to its underlying asset value. But as he said many years later, once he came to realize his mistake and finally exited the business:

Berkshire Hathaway’s pricing power lasted the best part of a morning.

Our preference is to own businesses that have been proven over many years and cycles. The average age of our businesses is over 70 years, with the oldest dating back to the end of the US Civil War. They have been tested through wars, product cycles, recessions, political upheaval, inflation and financial crises. The competitive advantage in our portfolio is evidenced by an operating margin of 27 per cent and a return on invested capital of 18 per cent - both over 2x the average listed business. It is interesting to note the average listed business earns a return of 9 per cent - not far from the level equities have actually achieved over the long term.

Over time it is hard for an investor to earn returns that are much higher than the underlying businesses’ return on invested capital”. Charlie Munger

Aggressive management or those who allocate capital poorly

Unfortunately, it is a fact of life that the people who end up running businesses are often no “shrinking violets”. They are usually very confident in their ability and their normal starting point is to aggressively “grow the business”.

This can often involve straying away from their core competence into new areas, where their “skill” will translate into superior returns to shareholders. The worst situation occurs where management take on a lot of debt at the peak of the cycle, pay an inflated price for an asset, heap goodwill on the balance sheet, only to reverse the deal many years later ― and more often under new management.

A classic example of this is GE, who took a very good industrial business and then ventured into credit cards, property, insurance, media … the list goes on. The end result was to take a AAA rated balance sheet and turn it into one that is now barely above junk status. Or closer to home – who can forget Woolworths ill-timed home improvement venture against the toughest of competitors, or even Bunnings themselves and their venture into the UK? Would it not have made sense to focus capital on the competitive advantage that made the company a market leader in the first place and then return excess capital to shareholders? And finally, my all-time favorite - the Vodafone purchase of Mannesmann at the peak of the TMT mania for $173bn, which saw Vodafone CEO Chris Gent earn a bonus of $16m for the “value” he created. In 2006, Vodafone quietly wrote the asset down by $28bn, but not before Sir Chris Gent received a knighthood for “services to the telecom industry.” I wonder whether he should have received the highest German accolade “for services to the German pension fund industry.”

To quote Michael Porter, the doyen of competitive advantage:

The biggest impediment to strategy and competitive advantage is an overly reliant focus on growth.

By contrast, we prefer our management teams to relentlessly focus on competitive advantage, customers, employees, communities and reinvest back in the business for the long term. And once this is done, to make sensible bolt-on acquisitions, pay dividends and buy back their stock when it is decent value. The last trait is very hard to find – there are very few management teams who treat buying their shares like they would any other acquisition. For most management teams, the logic is if I can borrow at, say 2 per cent, as long as I pay no more than 50x earnings – this enhances earnings per share. And unfortunately, most management teams will happily buy their stock in bull markets using cheap debt, only to stop this when their shares are cheap, as this is the “prudent” thing to do.

Buying businesses at prices that are well above their fair value

Even if one buys businesses that have superior economics, strong balance sheets and are well managed – even the most disciplined can be lured into paying inflated prices, especially in the upper reaches of a bull market. The narrative always follows a similar pattern that excess growth will last forever, interest rates will never rise, the company has changed (very few do), the company deserves a lower beta and the list goes on. When valuing companies, we do not change our discount rates, terminal growth assumptions, or market multiples, preferring to use “through the cycle” value inputs. Neither do we use a weighted average cost of capital (WACC) or beta to justify higher prices. Read any book by the doyen of valuation, Aswath Damodaran, and he will argue that if you are to drop your risk-free rate, you should also drop your terminal growth rate. This makes sense as a lower risk-free rate suggests a lower nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate. Yet, in the upper reaches of a bull market, it is not uncommon to see lower risk-free rates and higher terminal growth rates to justify valuations!

Conclusion

So, to return to the original client question posed at the beginning of this article: “How do I sleep well at night with only 10-15 stocks?” The question assumes that I would sleep better if we owned more stocks. Well, to do that, we would have to add lesser quality names or those with lower expected returns. Would I sleep better then? It would decrease our research intensity, whilst potentially lowering the quality and/or the expected return of the portfolio.

I could load up on “cheap” bank stocks but would now be exposing myself to balance sheet risk ― at 20x geared, these businesses can literally go to zero as we saw in the global financial crisis (GFC) ― as well as interest rate risk, economic risk and a large amount of regulatory risk (witness the halting of dividends in Europe recently).

Or, I could load up on “cheap” oil stocks, but I would be up late at night poring over demand/supply dynamics, vaccine developments and economic data. These are areas where the future is difficult to define and instead of allowing me to sleep better, it would have the opposite effect!

This is not our way.

Instead, we prefer to construct a portfolio of 10-15 high quality businesses, whose earnings have a very good chance of growing well ahead of inflation over a long period of time ― and when the inevitable bad times come, we know we own time-tested business models, fortress balance sheets and seasoned management teams that will get us through to the other side.

We may see share prices fall ― in some cases quite dramatically like the GFC or the March sell-off ― but for those with the fortitude to see it through, this is unlikely to be a permanent destruction of capital. This approach has served me well through hyperinflation in Zimbabwe, the TMT bubble, the GFC, the European debt crisis and more recently the COVID-19 pandemic.

For one known to like his sleep, it allows me to sleep well. And more importantly, our clients too.