2022 has seen a marked shift from “growth” to “value.” This has seen a resurgence in both bank and oil stocks. The former is expected to see an improvement in profitability, as interest rates rise with tighter monetary policy, whilst the latter are expected to benefit from higher oil prices ― more recently accelerated by the situation in Ukraine.

At Claremont Global, we have never owned bank or oil stocks ― nor will we ever. In this article we explain why this is the case, why we think the argument of growth versus value is misplaced ― and why we prefer to think in terms of quality, growth, AND value.

Look to own the best businesses

On our website, we ask our clients to “Own the world’s best businesses.” There are two key words in this sentence – own and business.

We are not traders or market timers of markets or stocks, looking to profit from short-term price movements. Instead, we look to own some of the world’s best businesses for long periods of time, ideally forever and the deferred tax benefits that come with that. This puts us in an effective position to benefit from the growth in their profits over time, and the long-term compounding effect of those profits being re-invested at high rates of return.

Why not banks?

Our definition of a superior business is one that can grow at a faster rate than nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth, is blessed with a competitively advantaged product or service and earns higher than average returns on unlevered capital.

Banks by their nature are the drivers of economic growth, and as such cannot grow faster than the economy over long periods of time. At best they can expect to grow their deposit bases and profits in-line with nominal GDP growth. Their products are effectively commodities with low switching costs and this is reflected in very low returns on unlevered capital.

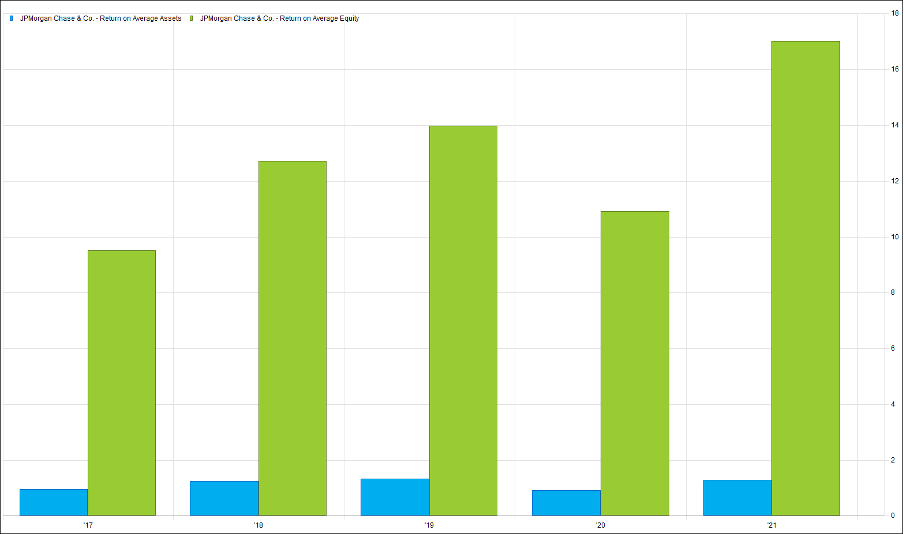

Over the last five years JP Morgan (widely admired as a best-in-breed bank) has averaged just over 1 per cent return on capital. This has then been levered over 11x to achieve an average 13 per cent return on equity.

Source: FactSet

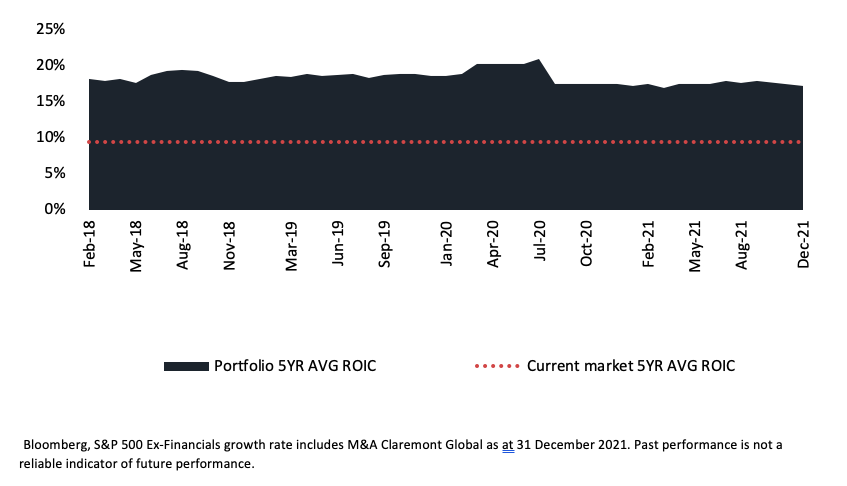

At Claremont Global, our businesses consistently earn a high teen return on invested capital, with very low levels of debt ― across the portfolio we are almost net cash. As for growth, we believe our portfolio of great businesses can deliver double-digit profit growth and at a rate that is possibly 2x the growth of the average listed business.

Source: Claremont Global

In good times, bank profit growth is not much better than the average business, but in bad times their high level of leverage leaves banks very exposed to the vagaries of consumer confidence, liquidity, and regulation.

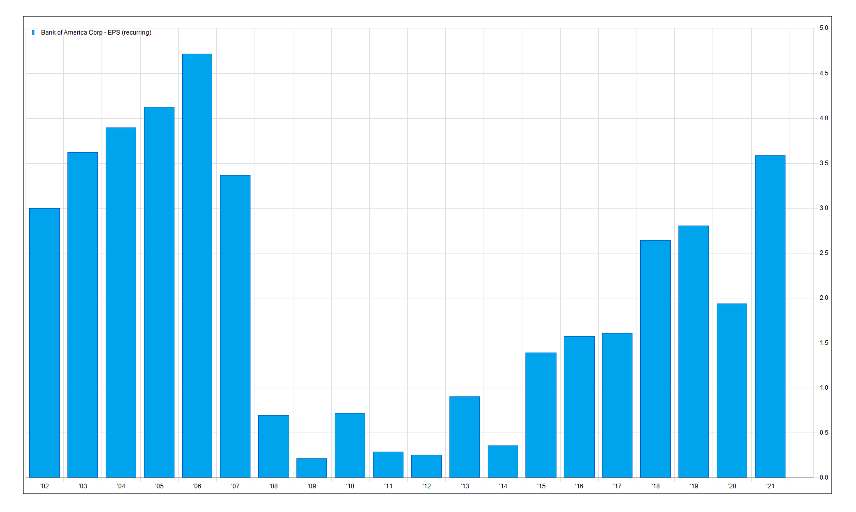

In an extreme situation like the global financial crisis (GFC), banks require large infusions of capital to buttress balance sheets and confidence, whilst regulators limit and/or suspend capital returns to shareholders in the form of buybacks and dividends. If we take the case of Bank of America, the massive equity dilution caused by the GFC, has resulted in the current earnings per share being below the rate it was in 2006!

Source: FactSet

In summary, banks do not pass three of our investment hurdles:

- organic growth faster than nominal GDP growth;

- high returns on unlevered capital; and

- low financial leverage.

The investment case against oil stocks

By definition, oil is a commodity with no pricing power and whose consumption over long periods of time is linked to nominal GDP growth. In the main, oil stocks have reasonable returns on capital and generally run strong balance sheets, but their profits are linked to the price of oil – something experience has taught us we have very little expertise in forecasting.

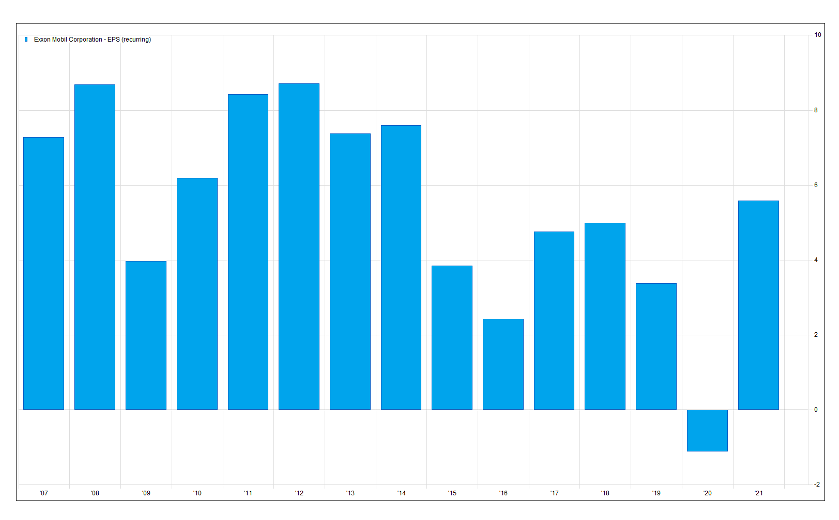

Indeed, in 2014 it was a commonly held view amongst “experts” that the oil price would remain above $100 indefinitely ― only to see the price collapse by 70 per cent with the advent of shale oil. Looking at the graph below shows that Exxon is still earning less than it was in 2008.

Source: FactSet

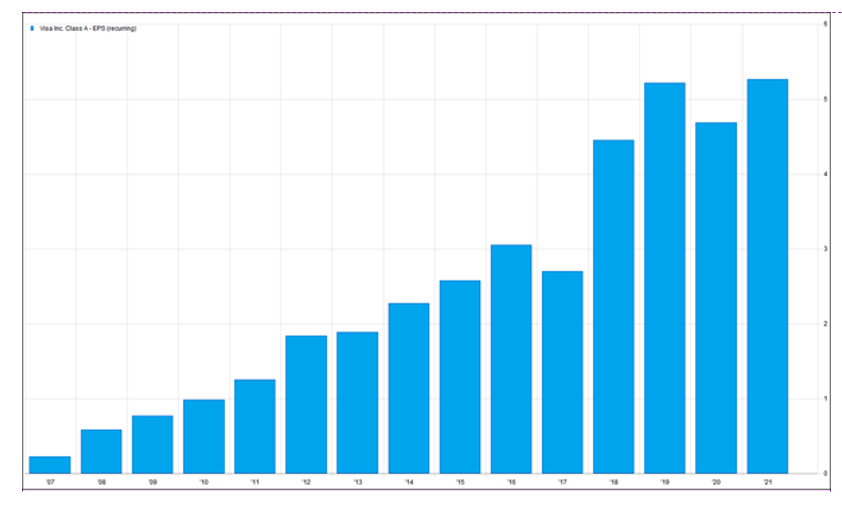

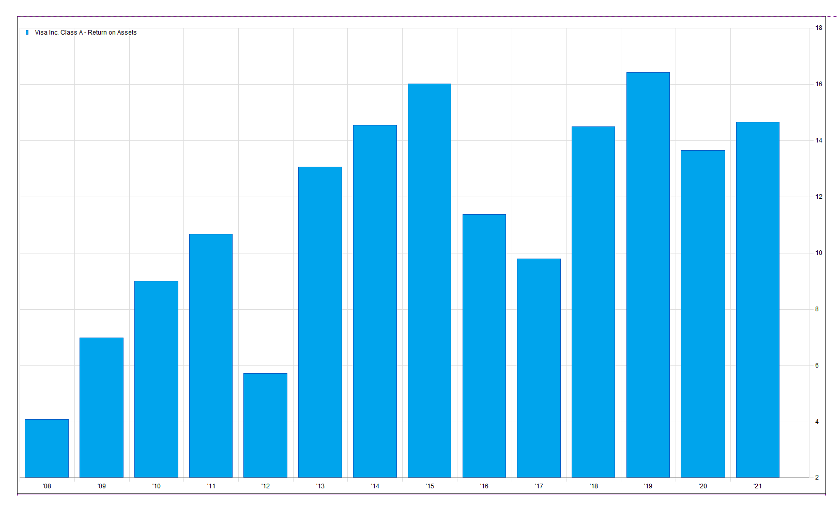

By contrast, if we look at the earnings progression of our largest holding Visa, the business has consistently grown ahead of nominal GDP growth and its earnings show a steady upward progression, as do returns on capital.

Source: FactSet

Source: FactSet

Whilst we won’t argue the possible merit in the short-term trading of bank or oil stocks, these are not businesses we want to own.

At some point in the future, we will need to make accurate forecasts about interest rates, economic growth, oil supply and demand, as well as an accurate prediction on the politics and policies of a phasing out of oil in favour of a more environmentally friendly solution to our energy needs. We are happy to admit we don’t have the specialist capacity or mental bandwidth to do so.

We are only looking for 10-15 mispriced businesses

Which brings us to our final point and one much loved by large parts of the financial community – quality growth stocks are expensive and it’s time to buy “value”.

Our view is that large parts of the growth universe are indeed expensive. In 2021, we did see a welcome shake out in some of the more speculative areas of the market, including many concept stocks with limited profits having fallen over 50 per cent. But even after this – there are still large parts of our investment universe with elevated valuations.

However, at Claremont Global, we are fortunate that we are only looking for 10-15 businesses who we believe can get our clients to our targeted 8-12 per cent per annum return over the next five years with lower-than-average levels of risk. And that return is simply a function of earnings growth, dividends, fees, and movements in the multiples of the businesses we own.

In all our valuation work we use through-the-cycle assumptions, and as such, we did not lower our discount rate in recent years to justify higher valuations. In addition, all our multiple assumptions are based on long-term average multiples (5-10 years) as opposed to recent history.

As a result, we are now not hurriedly raising our discount rates or bringing down our multiple assumptions. This discipline kept us out of the speculative areas of the market in 2021 – both in terms of unproven business models, as well as great businesses on our universe with very high PE ratios.

To conclude, we believe it is futile to think in terms of growth or value. We like to own businesses that will both deliver growth AND value. As usual, Warren Buffett puts it better than we can:

Most analysts feel they must choose between two approaches customarily thought to be in opposition: “value” and “growth.” Indeed, many investment professionals see any mixing of the two terms as a form of intellectual cross-dressing. We view that as fuzzy thinking (in which, it must be confessed, I myself engaged some years ago). In our opinion, the two approaches are joined at the hip: growth is always a component in the calculation of value. In addition, we think the very term “value investing” is redundant. What is “investing” if it is not the act of seeking value at least sufficient to justify the amount paid? Consciously paying more for a stock than its calculated value – in the hope that it can soon be sold for a still-higher price – should be labelled speculation (which is neither illegal, immoral nor – in our view – financially fattening).

In the short-term, we know it is quite possible that not owning bank or oil stocks will lead to temporary under-performance versus an index. However, over a longer time frame we think eschewing these industries ― in favour of owning faster growing and more predictable earnings streams ― is going to give our clients a higher probability of achieving our targeted return of 8-12 per cent per annum.

Most importantly, this will be within the confines of a strong balance sheet and commensurate with lower levels of business risk. This lower level of business risk allows us to sleep well at night (even in the very uncertain climate) and most importantly, allows our clients to do the same.